Why Current Pain "Management" Is Totally '80s. And How To Do Better.

A few choice takeaways from our recent paradigm-shifting course: Beyond Pain Education.

How I look when I hear old-school clinicians saying things that create fear about pain. Credit: “Stranger Things”

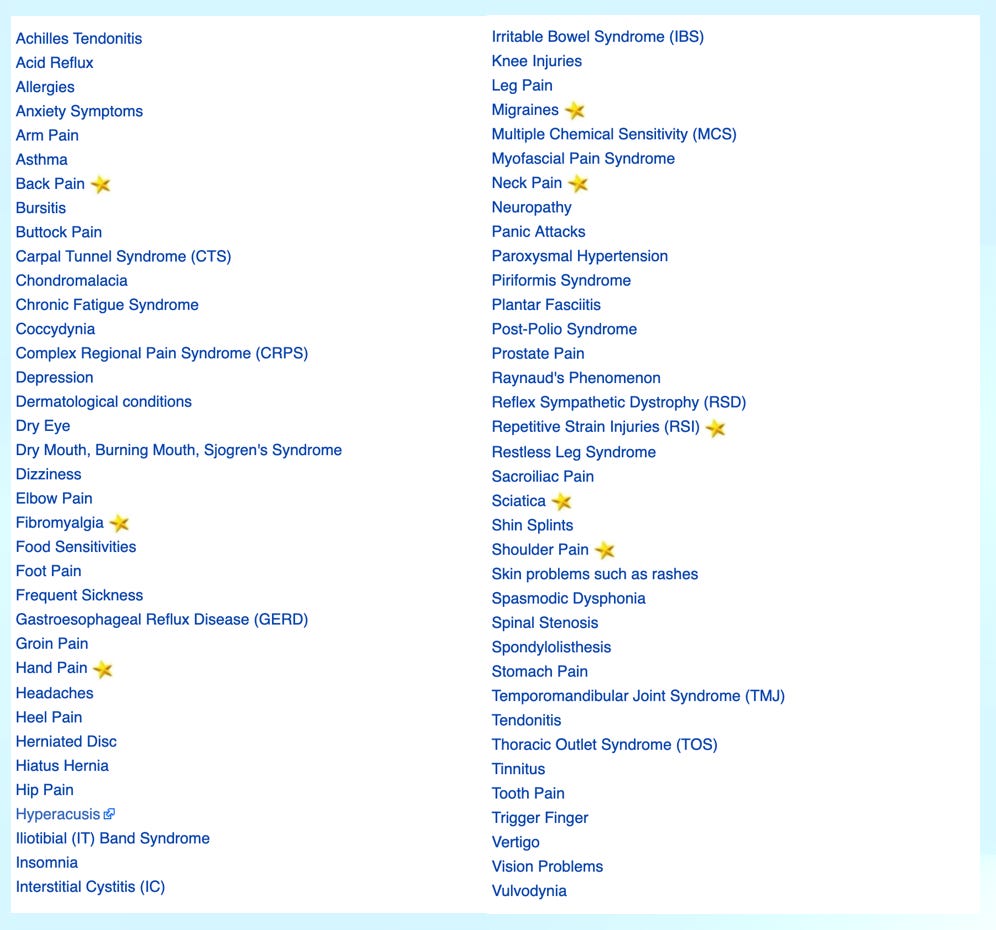

Don’t get me wrong. I loved the 80s. The fashion, the music, the style. It’s the decade in which I “grew up” and, as such, I have many fond memories. But 30 years later I now realize that time in history birthed the start of an important paradigm shift as fledgling novel pain science emerged. 3 decades later, we have robust evidence that pain is not what we thought it was. Forward-thinking clinicians are revolutionizing the way chronic symptoms are conceptualized and treated (see the list of chronic symptoms that are often not medical conditions but rather driven exclusively by the brain - below). But sadly, most clinicians are still treating pain as though Miami Vice is still the most popular show on TV. Luckily, you know better and can become a better advocate for yourself and your loved one’s heading into 2023 and beyond.

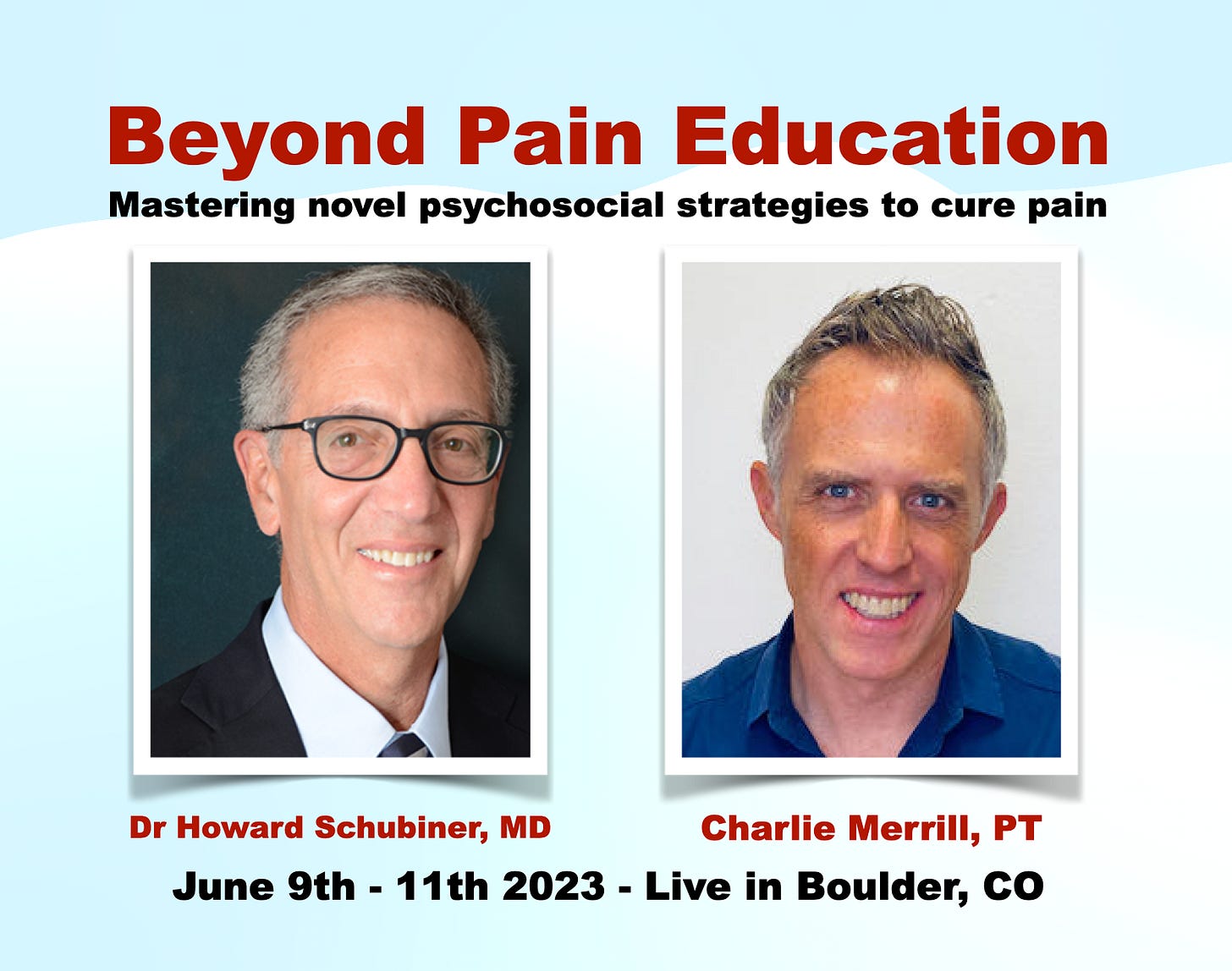

Pain is a protector. When we understand pain, we understand ourselves. Pain is the thread to our feelings. It’s a barometer for what’s going on inside of us physically and emotionally. Essentially it’s VERY effective at letting us know when something in our lives is “off” or not going the way we want it to go. Dr Howard Schubiner and have been teaching clinicians and people about the new science of pain together for over 5 years and have trained over 100 clinicians across the globe.

Our course distills and synthesizes the best evidence and clinical strategies from multiple disciplines and treatment approaches into a simple model that stems from a few basic ideas.

The brain is in charge of all pain.

Pain is a protector.

Pain does not always mean injury. Even when it’s acute or new.

Pain is fueled by fear.

Psychological injury causes physical pain.

All physical sensations connect to emotion and vice versa.

Pain can be learned and become a subconscious habit.

Pain can be unlearned and cured.

We show clinicians these novel ideas on day 1, and then again at the end of the course. Even the most pain science-informed clinician has doubts about at least one of these ideas on day 1. But at the end of the course, after dozens of clinical stories, personal experiences, a healthy dose of science, and seeing what’s possible with their own pain, clinicians can’t unsee the truth about pain. I’ve had clinicians tell me they felt angry when I started to debunk myths about pain and began to deconstruct the paradigm under which they’d been practicing. We all have cognitive dissonance and resistance to change. And of course, clinicians deal with confusion about how to move forward with this new paradigm. Physicians and Physical Therapists only get a few hours of education about pain over 3-4 years of school. So when we start to deconstruct the old theory of pain and rebuild the new paradigm based on modern multi-disciplinary science, clinicians naturally have doubts and questions. Turns out these points of objection are what make our course so robust and lead to the best clinicians who offer the best clinical outcomes. These clinicians are forever changed by the hopeful narrative that emerges from our course. I wanted to share a few powerful takeaways from the recent cohort:

The changes we see in the body are usually a RESULT of pain (the brain being in a state of danger alarm) rather than the cause. There are times when nociception (raw information from the body-not pain yet) travels up to the brain because there was an injury. Think about an ankle sprain, a bad car accident, a bike crash, a broken bone, joint dislocation, burning yourself, or stepping on a sharp object that cuts you. In these cases, there’s tissue injury that needs to heal. Upon receiving that information, the brain does its job by creating a healing cascade including an output (or sensation) of pain along with the appropriate swelling, redness, warmth, weakness, or whatever it feels is right based on the information it’s getting from the body. These changes encourage us to rest in the short term, see the doctor or physiotherapist, and do whatever is needed to heal up and move on. But as I said earlier, most pain is not due to injury. In these cases, what’s fascinating is that while pain without injury is subjectively the exact same pain (because all pain is real), the physical changes we see on exam don’t match the pattern we’d see if there was an injury. It’s as if the brain doesn’t know how to reproduce the same output when psychological stresses and fear and driving symptoms, even though that body part actually hurts as though it was injured. These changes appear more random, don’t follow a pattern, or are simply normal for that person (they were already there). Mostly these changes include de-conditioning and adaptive change from disuse and avoiding moving also result in body changes. But these changes are not dangerous, nor are they primary drivers of pain. Remember the brain is responsible for all pain, regardless of the cause! So you might have very real, stiffness, weakness, and even swelling in your body But in the absence of an injury, treating the “result” of pain rarely leads to lasting relief. Clinicians see better outcomes if they focus on psychological and social factors while reducing fear about moving by giving people the green light to do so in whatever way each person likes to move. Fortunately, most de-conditioning and adaptive change resolves with less fear and healthy movement. Below my colleague and brilliant pain scientist Dr. Lorimer Moseley talks a bit about the difference between pain and nociception in his amazing snake bite stories below.

When it comes to pain, emotions are meant to be expressed, not regulated. Here’s a story to illustrate this point. A few years ago, my 9-year-old son had a sudden onset of hip pain so bad that he couldn’t walk when we traveled to Tokyo, Japan as a family. We had traveled by air, train, and bus thousands of miles from home and, on the second day of our trip, were at an incredible Onsen (hot spring) near a volcano north of Tokyo. All 3 of my kids were so excited to be there and my son was joyful and playfully parkouring (jumping and bouncing) off of things all day. We checked into our lodging and, as a family, headed out for a 5-mile hike around the volcano. About 10 minutes up the trail, my son said, “Pop my hip hurts and I can’t put weight on it without pain”. I asked if he’d hurt anything earlier the day by landing funny, jumping off something that hurt, or tweaked it in any other way. But he was flummoxed. I encouraged him to stretch a little and squat a few times to move through it but the pain didn’t change. So we decided to head back to our lodge and eat instead of hiking. On the way back down the trail, my wife and the 2 girls went ahead. I held his hand and reassured him. I said, “Hey buddy, sometimes when we have pain in our body it’s because we have big emotions about something. I wonder if anything is coming up for you. Can we just walk for a second quietly so you can check in and see if there are any feelings?” Now it’s important to say that I’m remarried and that his birth mom was thousands of miles, a bus, train, and airplane away back in Boulder, CO. He was as far from his mom as he’d ever been and this was day 2 of a 3-week trip! Within 60 seconds of my question, he started sobbing and broke down in big crocodile tears. We sat and I asked him “What’s going on, buddy?” He simply said “I miss my mom so much” talking through his tears. He cried for a few minutes and I encouraged him to be sad. We talked about it and I reassured him, shared compassion, and encouraged him to do the same for himself as we walked back to eat. After a 30-minute lunch, he jumped up and said “ok let’s go, I’m ready to hike”. We hiked for 2 hours and his hip never bothered him again. Part of the process of unlearning pain involves identifying related emotions and not just talking about them, but actually expressing them. The brain often prefers pain to emotions. It’s a helpful distraction in that way. So this can be intimidating for most, especially with harder emotions like anger. But all of our feelings belong and should be honored. It’s when we subvert, overly regulate, bury, or ignore our feelings (as many of us were taught when we were young) that they express as physical symptoms. Below is an example from the Pixar film “Inside Out” where the character Sadness helps Bing Bong (The imaginary friend of the little girl, Riley, who is the main character) attend to and express his sad feelings, despite the character Joy’s attempt to try to suppress them. In this great film, emotions including anger, disgust, fear, sadness, and joy are all characters in Riley’s head.

Credit: “Inside Out”, Pixar

Your brain is altruistic in its motivation to keep you alive and thriving, even when it doesn’t feel that way. If you read my prior post discussing predictive processing, you might remember that the brain is always predicting what’s going to happen next in order to keep us alive and safe. If you’re driving on the highway and you see brake lights ahead, your brain might predict that slowing down is wise and you’ll press the brakes. If you walk into a dark room, your brain might predict that you’ll fall or run into something and so you’ll turn on the lights. These predictions are important for survival. Similarly, pain is critical for survival. A small number of people are born without the ability to experience pain. While this sounds nice at first, most of those kids die early because they have no feedback from the environment about what’s safe vs dangerous. So pain is a normal, universal, and a critically important sensation when it comes to living fully. It’s just not designed to stay on after the threat has passed. The challenge is that brain does not speak English. So the brain prefers pain as a way to alert us when something isn’t working in our lives. If you read my last article on personality traits, when we’re living our lives based on our conditioning from childhood (when our personalities formed), stress and emotions can accumulate over time. Because this ongoing danger is not like driving in traffic or walking into a dark room, the experience of pain is the most common way for our brain to deliver that message. Our personality traits tend to drive automatic behaviors that often cause stress and big feelings, and because we learned emotions like anger, sadness, grief, guilt, and shame are scary and dangerous, pain is a far more socially acceptable output for the brain to choose; and is it ever effective and getting our attention! The point of this takeaway is to offer you a more compassionate view of your brain and body so the next time you have symptoms, you start from a place of curiosity rather than reactivity. Fear is a normal initial response to pain. But as you start to re-conceptualize your symptoms, as we teach in our course, the insights you gain can reduce fear and lead to wisdom. Alan Gordon, LCSW wrote an excellent book about this process called “The Way Out”. It’s a quick read and full of great stories and strategies.

From a physical fitness perspective, the best way to prevent injury and pain (remember they’re not the same) is to expand your movement vocabulary. Just like a robust language vocabulary allows you to speak, write, and communicate well, a large movement vocabulary allows you to navigate a sometimes unpredictable world with ease, grace, and confidence. First, there are no “bad” or “dangerous” movements but rather only movements your brain either learned are dangerous or that it doesn’t recognize, yet. As human beings, we’re unique in that we’re capable of training our bodies to do and adapt to amazing things. Think of Cirque de Sole, the Olympic Games, Ultra distance running, CrossFit, Gymnastics, and so many of the other incredible feats the human body can do. The SAID principle, or Specific Adaptations to Imposed Demands, hypothesizes that our tissues (muscles, bones, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and nerves) gain fitness based on what we ask of them. This is a result of the brain receiving new information from the environment thereby stimulating an appropriate response to prepare the tissues assuming the physical stressor will likely happen again. This is how we gain fitness and skill In the process, new neural connections are created assuring familiarity and thus readiness the next time we’re in that situation. What’s cool about neuroplasticity is that these connection are being created, strengthened, or made dormant moment to moment. While the brain likes some amount of novelty and surprise, it prefers familiarity and safety creating rules and patterns to stay efficient. Of course, the brain and body also get better at certain movements and skills with practice. So it can get really good at habitually doing things a certain way. So when faced with some new physical stressor the nervous system doesn’t recognize and/or which it sees as a threat, pain and even sometimes injury can result. Pain happens as an early danger alarm to warn you, resulting in muscle tension and guarding. Injury happens when the brain perceives the threat to be too big (the muscles might overreact creating damage) or when the load is so fast or high that the brain doesn’t have a chance to react (tissues get injured before the brain can react). In either case, the brain is reacting to an unfamiliar threat. So the obvious path to building a reliable movement vocabulary is to expose your body and mind to the things you want to be able to do: ie. Practice your discipline regularly, with intention, focusing on movement quality to find mastery and automaticity. A powerful way to expand your movement vocabulary is to diversity those practices; ie. Different types of yoga, running on different terrain, dance different styles, essential improvise and explore different ways to move in that familiar practice. Another way to expand your movement vocabulary is to mix up your movement practice completely!; ie. Pick up a different instrument, add golf to support your tennis, dance or go yoga to balance running, do pilates to enhance cycling, or add frisbee to your soccer warm-up. You can also practice things like falling to make it safer when it happens next, tumbling to improve getting up/down to the ground, being upside down in a handstand to reduce sensitivity to that position, spinning around to normalize vestibular function, and fast reactive movements to enhance reaction time. Essentially think about what unpredictable situations and positions you might experience in your life and do them as part of your movement practice. This way, the next time they show up suddenly and unexpectedly, your brain will be like “Oh I remember this. This is familiar. Got it. No worries”. Here’s an Instagram video with a few examples of how I work play, novelty, fun, and variety into my movement practice. Maybe you’ll find a few to try this week.

The takeaways from our course are many and I look forward to sharing more insights in future posts. Don’t miss the latest and greatest insights into the intersection of pain and performance! Please take a second to follow me on Substack by subscribing; and if you, or someone you love, benefitted from this article please support my writing with a donation of any size so I can continue to do the deep of collecting science, resources, stories, images, and more from around the world. I want you to be an expert so your clinicians don’t have to be. I appreciate you reading to the end and welcome your feedback and ideas for future articles. Wishing you all the best and hope to connect with you soon.

Wishing you love, growth, and a just right amount of pain to facilitate both.

Charlie